By popular demand, Thor explains the colorful variety of stones found in our Pacific Northwest.

Sara asked me to contribute a blog on our recent obsession with rock tumbling. First a little prologue about the local geologic context, and why we have such a variety of stones here in the Pacific Northwest:

A few hundred million years ago, there was no Washington, Oregon, or California. The ocean lapped up somewhere in what is now Idaho, Nevada, etc. There has been a subduction zone on the west coast of North America, which means that Pacific Ocean crust has been sliding under the North American continent all that time. The sliding is not smooth, however; the rocks get stressed and bend and then break in earthquakes, gradually lifting the crust and producing mountains. The descending crust melts when it gets deep enough, and the rising hot magma produces volcanoes and also cooks the surrounding rocks. In addition, the Pacific Ocean crust has lots of islands and seamounts. These bumps get scraped off when they hit the continent and gradually grow the continent westward in a process known as continental accretion. All of this squeezing and heating changes rocks in a process called metamorphism. Metamorphism can turn a rather blah sedimentary rock (rocks formed from lake, ocean, or desert sediments) into a beautiful stone with garnets and mica. So, we have distant rocks coming from the west and being metamorphosed, magma and volcanoes rising, and the whole mess being squeezed and uplifted into mountains that form a rich source of varied rock types. Then we had glaciers cover the whole state to a depth of a mile or more. If you flew over Washington 15,000 years ago, all you would see would be ice and the tips of the Cascade Mountains peeking out. The glaciers carved out chunks of rock and carried them downslope toward the ocean. We’ve had numerous glacial advances and retreats, so these rocks were dumped pretty much all over, and their source may have been hundreds of miles away. This means when you browse through the pebbles on the beach you are looking at volcanic rocks, granites, sedimentary rocks (sandstone, shale, limestone), and metamorphic rocks that may have originally come from hundreds of miles away. That’s why I love polishing beach rocks; each one tells a story.

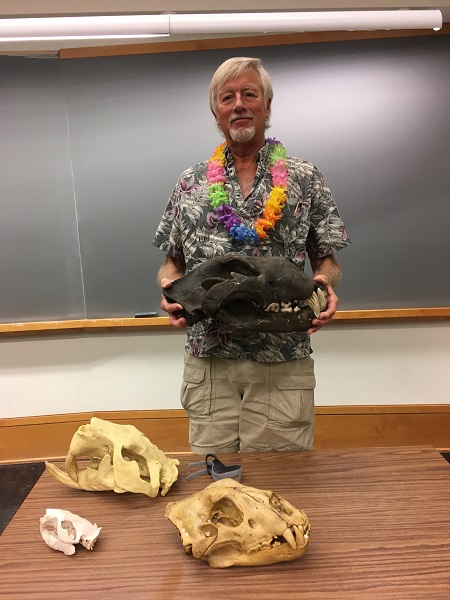

I started collecting fossils when I was a kid. Around age 10, I would load some tools and a lunch into an old army pack my father gave me and hike through the woods to a local fossil locality. That is what kids did then; leave the house to wander around and get in trouble. But you better be home for dinner! I pursued this passion into high school and college, eventually getting a degree in geology and becoming a college professor teaching paleontology and geology. Sara insisted I add this photo of my last on-campus teaching day after 40 years, holding a cast of an extinct American lion skull:

Fossils were my specialty, but I always liked rocks. I would sit on the beach and look for pretty pebbles and try to classify them as igneous (once molten, like lava or granite), metamorphic (changed by heat and pressure), or sedimentary (sediment laid down by wind or water).

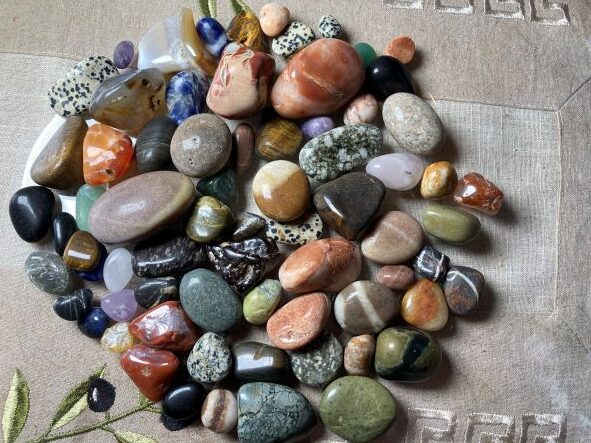

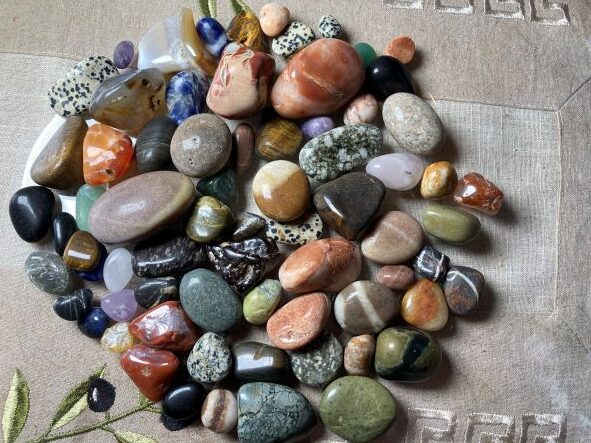

Sara and I sold our house in May and have been living in a rental while we build our dream house. All my tools and crafty things are in storage (the permitting process was MUCH longer than anyone anticipated), and I was bored, so on a whim I got a rock tumbler. The tumbler came with a pack of stones to polish: agates, tiger’s eye, lapis, etc. These polished up very nicely and are quite pretty, but they are also fairly common, i.e. they are the rocks that everyone polishes. They all look pretty much the same. So on a whim I threw in some beach pebbles. Oh My God, what a revelation that was! Those dusty, fairly nondescript stones turned into beautiful pearls, each with a different story. No two quite alike.

Let me introduce you to a few of these local beach rocks. Rocks that have a white band are what Sara and I call a “wishing rock” because if you throw it over your shoulder into water, your wish is granted. Works every time for us. The one below is sandstone (the faint dark horizontal band is a layer of the original bedding) that has been baked and squeezed a little (slightly metamorphosed) to make it very hard, and then it was fractured, and the gap was filled in with microcrystalline quartz creating the white band.

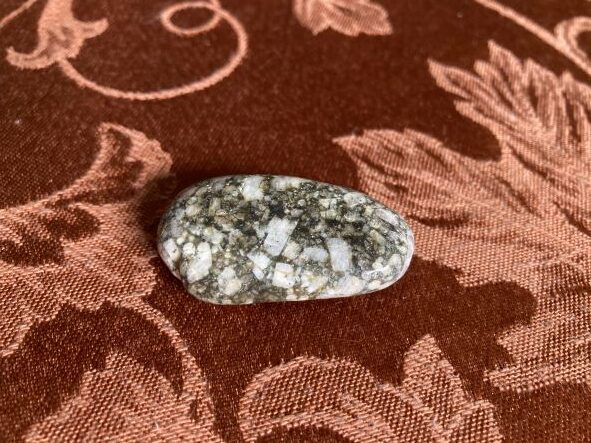

Sometimes the quartz layers intersect to make interesting patterns, as you can see in this pretty metamorphic rock.

Igneous rocks were once molten. When a volcano spews lava, it cools pretty fast and does not have time to grow large, visible crystals. That is why the volcanic rocks around Mt. Baker just look black. But if the molten rock stays underground and takes a long time to cool (over thousands of years), it will grow visible crystals. The higher temperature minerals form first, followed by lower temperature minerals, until the whole thing is solid. This is a beautiful example of an igneous rock that took a while to cool. The large white crystals are feldspars surrounded by smaller crystals that I can’t identify.

Sedimentary rocks typically have bedding, i.e. layers of sediment formed by deposition. In this one you can see very thin layers of silt or clay. The small grain size and the thin layers tells me that the sediment that formed this rock was deposited in very quiet water, a large lake or maybe the deep ocean. The fact that you can see the layers at all suggests that the environment was largely devoid of life, because if there were animals living in the sediment, their movement would have disturbed the mud and mixed it up. This is a process we call bioturbation. It is common for large lakes to become anoxic at the bottom in the summer, and this has even happened in the sea in the past. It is especially cool to think that this rock may have formed in the sea or on an island thousands of miles away and then been transported here by continental accretion.

This is the same rock on its side where you can see the bedding a little better.

This rock is one of Sara’s favorites. It is a sedimentary rock. The gray material was once a layer that had partially solidified and then was disrupted (possibly by an earthquake or some other disturbance) and broken into angular fragments (brecciated). Cool. (Note from Sara: The rock is actually a lovely grayish green – see top photo at bottom of image.)

The rock below does not have much of a story, but it is beautiful. It is a piece of microcrystalline quartz, probably a remnant of a quartz vein as seen in the wishing rock at the top of the page. The fractures are stained with iron-bearing minerals, giving it a nice marbled look.

Polishing rocks has been both a blessing and a curse. We love admiring the beautiful polished stones and feeling their sublime smoothness. But now we can’t take our eyes off the ground when we walk, looking for more tumbler candidates. Every time I sit on a pebble beach, the rocks whisper to me, demanding my attention. Look at the rough rocks below waiting their turn in the tumbler. What stories will they reveal?

*****

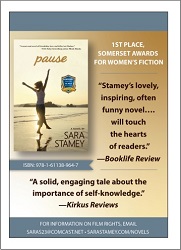

You will find The Rambling Writer’s blog posts here every Saturday. Sara’s latest novel from Book View Café is Pause, a First Place winner of the Chanticleer Somerset Award and a Pulpwood Queens International Book Club selection. “A must-read novel about friendship, love, and killer hot flashes.” (Mindy Klasky). Sign up for her quarterly email newsletter at www.sarastamey.com

Thanks for sharing – that was lovely and educational, too.

Thor says you are welcome!