Join Thor and me as we visit a Minoan cemetery and admire the painted larnakes — earthenware caskets — and grave offerings in museums on Crete.

NOTE: Of course, Thor and I had to make another trip to Greece, as he’s fallen as much in love with the islands as I am. This time, in addition to other island-hopping, I wanted to return to Crete after 37 years. My first months-long trip was as a hippie backpacker, camping in the ruins and falling under the spell of the mysterious, vanished Minoan culture. This time, I got to introduce Thor to “glorious Kriti” and research more settings for my novel-in-progress, THE ARIADNE DISCONNECT. This new blog series started October 19, 2019, and will continue every Saturday.

If you’ve been following this blog series, you’re aware that there is very little written history about the Minoans, so our knowledge is pieced together by experts from physical evidence of archaeology. I’ll discuss sacred rituals and artifacts in next week’s post, but the consensus seems to be that the Minoans honored the sacred forces of nature, as well as venerating an Earth Goddess similar to those worshiped in much of the Middle East of the time. They did not build elaborate temples or tombs such as those in Egypt, but in the early stages buried their dead in natural caves or group graves. Later they developed cemeteries with chambers to hold the larnax casket with the body, accompanied by grave goods. As Arthur Cotterell puts it in THE MINOAN WORLD, the dead one “has gone to the last resting place within the full bosom of the mother-goddess.” (pg. 184)

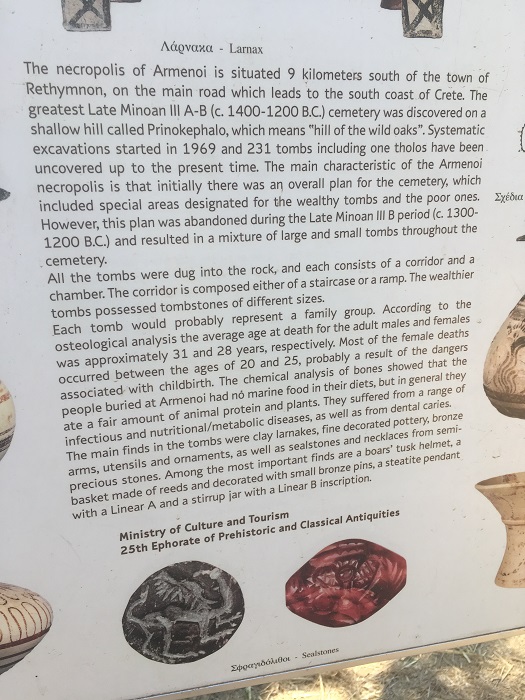

When Thor and I arrived on Crete, one of our first stops, just south of the port city of Rethymnon, was at the late-period Minoan cemetery of Armeni. At the end of our trip, we visited the famous palace complex at Knossos and toured the artifacts in the nearby Iraklion Museum of Archaeology, so here I’ll combine what we learned at both sites. First, one of the excavated tombs at Armeni:

It’s important to note that this cemetery combines graves from the Late Minoan period, before the takeover by mainland Mycenaeans, with graves from the period under Mycenaean influence and control. For example, one of the finds from Armeni is a boar’s-tusk helmet, definitely part of the mainland militaristic culture and not the earlier, mostly peaceful Minoan traders.

Some of the graves, apparently for the wealthier people, were larger, with deeper and steeper entrances. Here, I prepare to enter the gloom of the tomb:

We didn’t linger long with whatever ghosts might remain in the chamber.

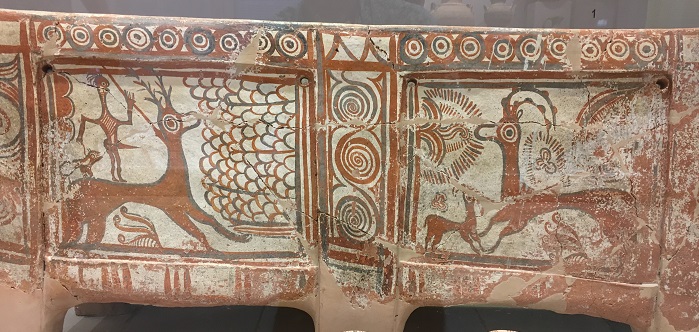

In the small but delightful Rethymno museum, we saw many of the artifacts unearthed from these tombs, including this beautiful larnax, or earthenware casket. The decorations remind me of those in ancient cave paintings that may depict shamanic or other ritual events, or simply hunting scenes. The animal on the right panel with curved horns is probably the native Cretan goat, or ibex. We weren’t allowed to photograph an even more evocative larnax, since it hadn’t yet been published.

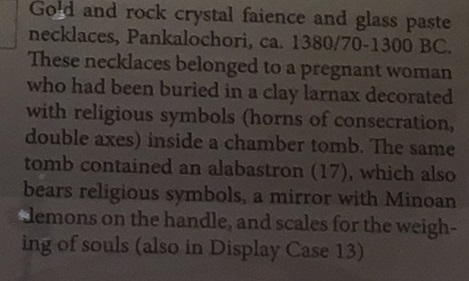

Some of the grave offerings from Armeni:

Bulls were important in rituals, and the symbology evolved into the “horns of consecration” that we saw at Knossos.

Thor and I did take a few moments to reflect, in the dark and quiet of the tomb, on the people who honored their dead with their labor and treasures, which remained here over thousands of years. The priestess vessels above are a type of offering found in other sites on Crete as well (we’ll see more from Knossos next week), their upraised arms honoring the sacred.

Again from Cotterell: “The land of the dead fused in the Minoan mind with the rich soil from which the plants and crops grow. Bereavement was an acknowledgement of the place that man had in universal growth and decay, the timeless rhythm of the great goddess and her lover, the dying god.” (pg. 184) More about the goddess and the dying god next week!

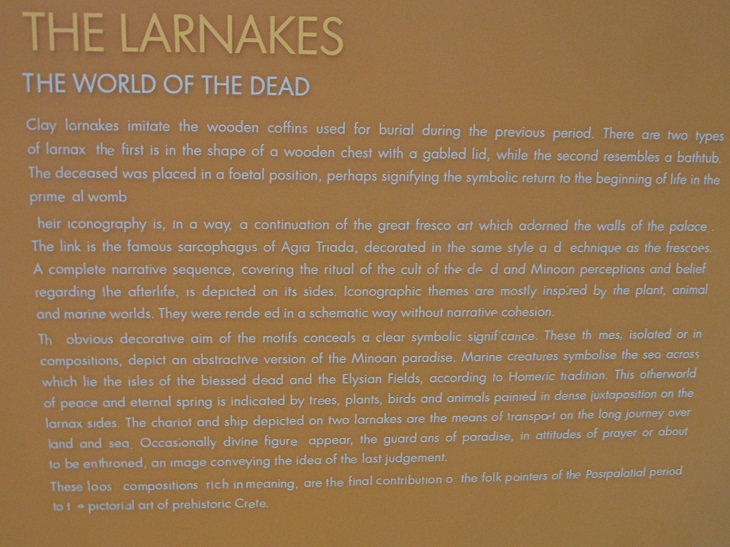

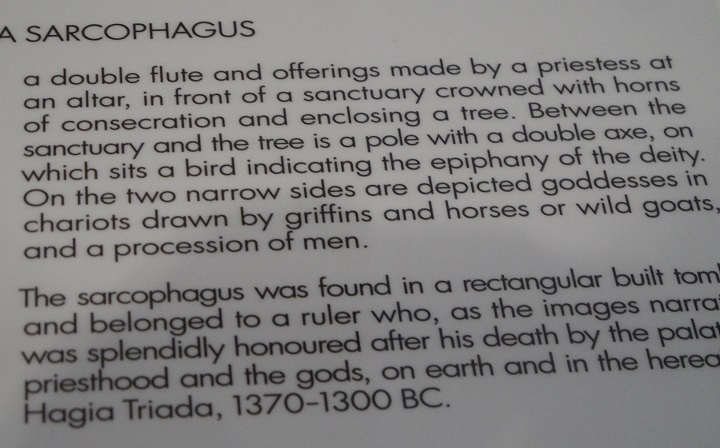

On to the museum at Iraklion, with larnakes from Knossos and nearby sites:

Some of them are more boxlike, with lids, while others resemble bathtubs. There is speculation that these might have been used as bathing tubs before being used as caskets, since some had drainage holes in the bottom.

Another larnax from the late 14th century BC showed some Egyptian influence. A dead man stands outside his tomb, as men brings gifts, a priestess pours a libation, and a musician plays the lyre:

Back at the Armeni cemetery, excavations were continuing to produce new artifacts. Some of the workers were marking out a new grid on the slope above the trenches we had explored, and as we wandered over they were taking a lunch break. When I mentioned to one of them that some of the small tomb doorways had the typical trapezoidal shape of Mycenaean gateways I had seen years before on the mainland, he confirmed my guess that these were the later tombs, dug after the arrival of the mainland Greeks. While we chatted and some of the workers rested with lunch and cigarettes, an older man in the shade of the trees was playing traditional Greek tunes on his boom-box and dancing a la “Zorba the Greek.” After all, the irrepressible Zorba was a Cretan. Why not dance to celebrate life and death?

Next week: Sacred rituals and artifacts.

*****

You will find The Rambling Writer’s blog posts here every Saturday. Sara’s latest novel from Book View Cafe is available in print and ebook: The Ariadne Connection. It’s a near-future thriller set in the Greek islands. “Technology triggers a deadly new plague. Can a healer find the cure?” The novel has received the Chanticleer Global Thriller Grand Prize and the Cygnus Award for Speculative Fiction. Sara has recently returned from another research trip in Greece and is back at work on the sequel, The Ariadne Disconnect. Sign up for her quarterly email newsletter at www.sarastamey.com

1 thought on “The Rambling Writer Returns to Crete, part 19: Minoan Burial Practices”